03/01/2014

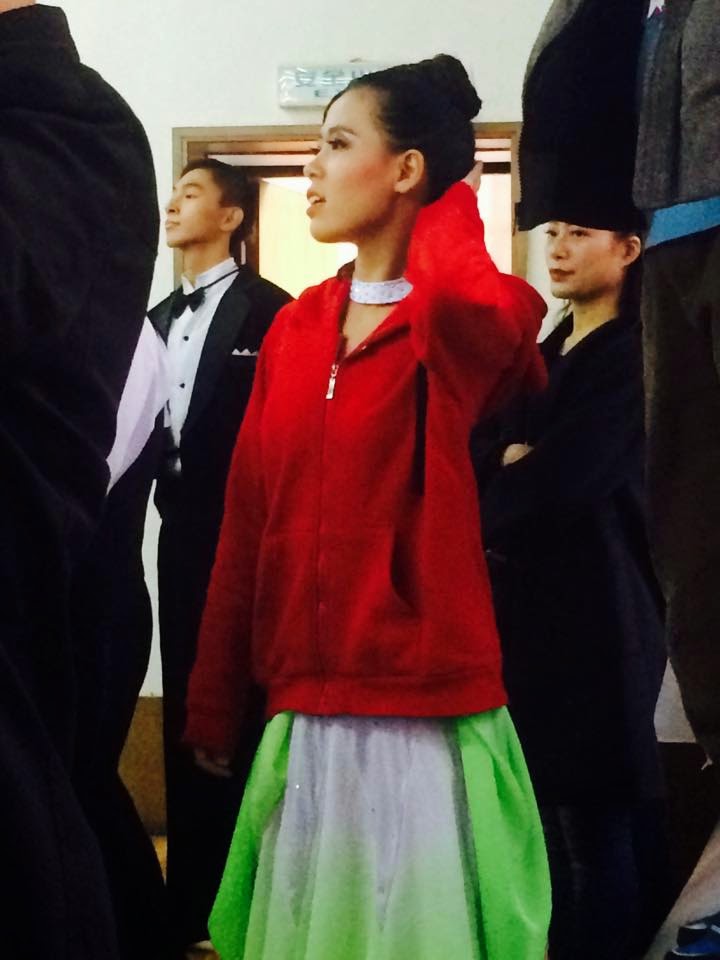

The girls fill the air with a vibrant energy as bright as

the sun which hasn’t come out to play today. They greet us with chai, laughter

and enthusiasm for the day hike we have planned. They are late, but it is hard

to be irritated with so much good humour and kind smiles.

The jokes and joyous chatter continue as we make our way to

the base of Shivapuri National Park where we are planning to hike. The girls

are training to climb Mt Everest base camp. The girls are part of the

organisation Shakti Samuha (the name

translates as power or strength and group or together – so it means roughly

that together we are powerful/strong) that seeks to prevent, rescue,

repatriate, rehabilitate and reintegrate trafficked girls from Nepal – some of

them are themselves survivors of human trafficking. Recently they received

funding for a group of girls to make the trek to base camp.

Two of the girls confide in me that it is their dream to

climb Mt Everest. For one young woman (19yrs), it has been her dream since she

was six years old. She tells me that at that time, she had learned about Pasang

Lhamu Sherpa in school and went home to tell her mother that she was also

going to climb Mt Everest. Her mother wasn’t too pleased though and told her

that it was too dangerous (the fact that Pasang died while descending from the

summit didn’t help to convince her). Despite her mother’s objections, the young

woman persisted and while base camp is a start, I believe that one day she will

make her dream a reality. Currently, she studies social work, but her

adventurous spirit shines through her bright and engaging personality. After

talking to her, I am convinced that she will go on to do amazing things with

her life; that she will continue to reach new heights and uncover unknown

horizons.

For another one of the team members, climbing Mt Everest is

a personal challenge. She is afraid of heights so she chose to participate in

this quest as a way to face and overcome her fears. She tells me frankly that

she doesn’t want to be afraid any more, that doing this climb is both a literal

and symbolic way for her to throw away her fear. I find her very courageous. I

also understand where she is coming from. I have spent the last 12 years of my

life practicing the art of letting go of my fears and jumping into the void of

uncertainty. After all this time, I can’t say that I don’t know fear; I am

still scared every time I get in my kayak; every time I enter a social

situation; every time I am in a new place or I try something new. I still get

scared, but I don’t let that fear paralyse me or prevent me from achieving my

goals. My companion may not have realized it yet, but I think that she has

already succeeded. By choosing to do challenge her fears, in a way, she has

already conquered them.

Before reaching the start of the hike, we get caught in a

downpour and have to take shelter in a restaurant. We enjoy an early lunch and

play a game while waiting out the rain. The girls who speak good English

translate for me and even though, I still miss a lot of the jokes, I am content

just to listen to their laughter. I am happy to be surrounded by so much

positive energy and good people. During the game, someone asks one of the girls

what is the most important thing to her. Her answer: education.

When the skies clear, it is too late to climb Shivapuri so

we meander our way through the hillside, slowly making our way back to town. Along

the way, the girls tell me about Shakti Samuha and the innovative work they are

doing to prevent trafficking

through education and intervention in rural communities in Nepal. They sing a

song for me about human trafficking that was written by a staff member at Shakti

Samuha and interpreted by a local artist to highlight and honour the work the

organisation is doing. They are currently looking for funding to record the

song and make a videoclip.

I go home feeling both inspired and invigorated. They call

them survivors, but the girls I met today are doing so much more than just

surviving; they are living, creating, growing, reaching, shining, conquering

and thriving. Once again, I am blown away by the women here; by their

resilience, integrity and good humour. I resolve to continue training with them and who knows, maybe there will be more opportunities to get involved with such a fantastic group of young women and such an ground breaking organisation.