21/11/14

A decision to hang out downtown with some friends turned

into a random afternoon exploring an art college where we watched some student

presentations and stumbled on a ballroom dancing competition. The competition

was a stroke of luck while waiting for the art class to finish preparing their

presentations we spotted some girls in sparkly dresses on the street below. We

went to investigate and somehow managed to sneak our way into the dance hall

(it was closed to the public). We found ourselves in the midst of couples all

lined up waiting anxiously for their turn to dance.

I found their faces most intriguing to watch: some looking

nervous and jittery; others with a fierce look of concentration; some were

counting during the dance; others had pasted a smile on for the judges. You

could usually tell how their dance had been judging by their faces as they came

off the dance floor: some looked close to tears while others were elated.

The girls’ outfits were also a point of interest: bright

swooshing skirts, open backs, glitter and sparkles everywhere, fake long lashes

and gelled hair with flowers and tassels woven in. Even after exiting the dance

hall, we stayed sitting on the sidewalk for a long time watching the dancers

coming and going. As we were leaving, the girls had changed into some more

carnavalesque outfits with flashy colours, short skirts with tassels, shakers

or frills and a bit of animal print.

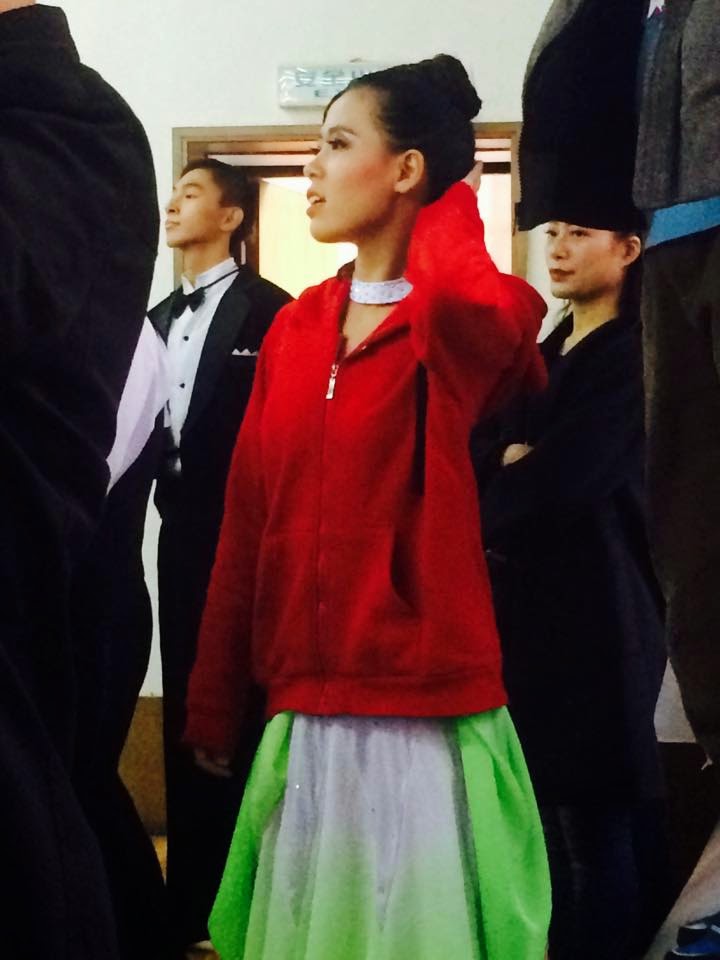

A dancer checking out her competition while waiting her turn.

photo credit: Frances Wintjes Clarke

One girl in particular drew my attention, because unlike the

others, she was not a stick figure. She had more Mongolian features with a very

round face, big cheeks, broad shoulders and wide hips. She had a very generous

smile and secretly I hoped that she would win. I wondered how the others might

perceive her: if she gets teased or discriminated against for her size (she was

about my size, so not fat, but big in comparison to most Chinese people) or if

it is seen as normal? I also wondered how much their appearances counted for in

the dance competition: were their appearance and outfits also being judged?

Were the costumes mandatory? What would happen if someone just showed up off

the street wearing no makeup and the clothes they wear to go to work and just

started dancing? Would they be judged the same way as the others based on their

ability as a dancer or would they be disqualified because of their appearance?

After the ballroom show, we found a group of breakdancers

practicing in a park. Their leader was a young woman with a peculiar hairstyle,

baggy clothes and visible tattoos. She was intriguing in part because she was

the first Chinese person I saw with tattoos and in part because she was one of

the rare women in China I saw that wasn’t girlish. Attitude usually comes

with being a breakdancer, but it was refreshing to see a woman not acting out

the role of a delicate flower for once.

On the way home, I chatted with a buddy about the film her

group had watched on the cultural revolution (Farewell

my concubine). As we discussed some of the horrors of the cultural

revolution, the buddy told me that Mao was not to blame, but that his wife, Jiang Qing, was responsible.

“According to official Chinese history [Jiang Qing] shoulders the blame for the

evils of the cultural revolution” while Mao remains their infallible great leader

who can do no wrong (Schaffer & Xianlin, 2007). Of course, there is

nothing surprising about the woman being blamed for history’s mistakes. And while

Jiang Qing certainly did do some bad things, it should be recognized that she

wasn’t acting alone.

While researching influential women in Chinese history, I

found that most famous women who at some point seized power were portrayed

negatively in the annals of history. Women like Wu Zetian and Cixi who were two

of the most powerful women in Chinese history are described as power hungry and

ruthless villains; however, as Wikipedia helpfully points out, “she was no more

ruthless than other rulers” at the time. It all comes back to the whole

double-standard thing where if a man acts aggressively then he is showing

strength and being a good leader, but if a woman acts in the same way than she

is labelled a villain and a b*tch.

Not to mention that women are often discredited by

attributing their success to their beauty rather than their skills or

cleverness. Both Wu Zetian and Cixi were considered beautiful and started off

on their road to power as concubines. Mao also had a preference for

young, modern, pretty women like Jiang Qing who started off as an actress and

became the face of the revolution as the head of the Communist’s Party

Propaganda Department (Ip, 2003). Myths like the four beauties reinforce

this idea that women must “exploit” their beauty and sexuality in order to gain

power by seducing, manipulating and even distracting their opponents. Under the

cultural revolution the “deployment of feminine beauty for political ends” was

known as the “beauty tactic” in which women used their appearance to advance

the political and ideological goals of the revolution (Ip, 2003).

Even today beauty plays a significant role in establishing

power and women in politics are often scrutinized and discredited based on

their looks. It all comes back to what our buddy said: that if a woman isn’t

beautiful enough, then no matter what she does it will never be good enough.

This has got to change. There are some brilliant and beautiful minds out there,

who regardless of their physical appearance, deserve to have their ideas, their

talents and skills recognized and appreciated. These people have something real

and valuable to contribute to the world and it both disgusts and saddens me

when their work is minimized and cheapened by superficial concerns. Like my

hypothetical dancer from before; she could be the most phenomenal dancer out there,

but if she doesn’t look the part then she probably won’t win the prize…

Ip, H.-Y. (2003). Fashioning Appearances: Feminine Beauty in Chinese

Communist Revolutionary Culture. Modern

China, 29(3), 329-361. DOI:

10.1177/00977004032

Schaffer, K. & Xianlin, S. (2007). Unruly Spaces: Gender, Women's

Writing and Indigenous Feminism in China. Journal

of Gender Studies, 16(1), 17-30. DOI: 10.1080/09589230601116125

Dancers and performers reliving their glory days in People's Park, Chengdu

No comments:

Post a Comment